The power of empathy and kindness

What this means

They can’t take away kindness.

This was a comment made by one member of the Leading The Lives We Want To Live group. Another replied:

…even though they may try to.

This exchange relates to the idea that, often, professionals want to be kind and empathetic but find their time and ability to do this squeezed.

However, the group also wanted to make it clear that kindness alone was not enough. It is not a substitute for professional, well-funded, care and support, and it should not be treated as such.

Valuing kindness and empathy alongside other worker qualities should be embedded in an organisation. People are asked to share their stories, but these stories can often involve frustration, anger, irritation and tears. Feeling safe to express these, and gaining understanding rather than feeling judged, involves trusting relationships. Encouraging workers to ‘walk a mile in the shoes’ of people who draw on social care, for example by bringing the experiences of people with care and support needs directly into training – while providing support for worker resilience – is a key way to develop (and value) kindness and empathy.

Workers might think differently if they could only visit the toilet three or four times a day!

Why is it important for the system to value empathy and kindness?

In this video, Katie Clarke talks about the importance of valuing empathy and kindness within the health and care systems:

The research

Across the UK, people who report high levels of life satisfaction are also more likely to report strong experiences of kindness in their communities (Wallace & Thurman, 2018). 63% of people agree that, when others are kind, it has a positive impact on their mental health (Mental Health Foundation, 2020). However, experiencing kindness (or not) can reflect wider inequalities. Wallace and Thurman (2018) found that Black and ethnically minoritised people are less likely to report strong experiences of kindness in their area, and those from more privileged backgrounds experience more kindness in their communities.

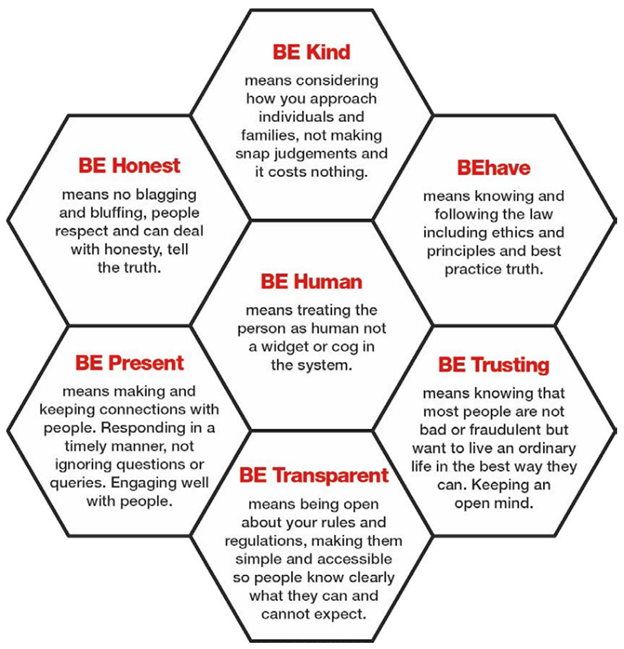

The Be Human movement, formed by people and organisations connected to In Control, published a 2021 report that researched the effects of older and disabled people experiencing automation, unfeeling responses, bureaucracy and confusion from systems designed to support them – which might be considered as the opposites to kindness and empathy. The study grew from the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, but also has resonance beyond it.

Arising from this project, citizens across the UK created seven principles for organisations to adhere to:

(Cockayne et al., 20210

Another project, the Kindness Innovation Network, analysed the conditions needed in organisations in order to enable kindness. It found there were often unspoken barriers to kindness that organisations needed to consider in order to embed kindness:

- Attitude to risk. If organisations were overly risk averse, they could create blanket and inflexible rules that overrode kind responses and created a lack of trust in human relationships to address challenges.

- Impact of regulation and professional guidelines. A frequent finding was that workers felt that, in order to be kind, they had to break rules – for instance, hugging people when they were not meant to, or giving out their personal phone number.

- Reluctance to let go of performance management. Because acts of kindness, and the impact they create, were hard to measure, they were not valued by organisations who valued quantifying worker performance.

- Fear of radical kindness. Organisations can worry that a kind response will have consequences that they are unable to manage - such as a higher number of enquiries, a longer time spent with people, or even that kindness was seen as being a ‘soft touch’ by people.

The Kindness Innovation Network also found other challenges when discussing kindness. The main one was that it could be hard to talk about kindness alongside cuts to the system (this reflects what one Leading The Lives We Want To Live group member observed: “How can we talk about kindness when the system is brutal?”). Another tension was observed in that kindness may be co-opted in order to rely on the voluntary work of individuals or communities, and therefore to withdraw services (Ferguson & Thurman, 2019).

What you can do

For everyone: Consider your job role against the seven Be Human principles, above. For each of them, ask yourself:

- How do I personally embody this principle in my work?

- How does my organisation embody this principle?

- What do I think needs to be improved?

- What do people with care and support needs say needs to be improved?

This can work well as a team exercise. Once you have your responses, pool them. You can then start to develop a plan based on:

STOP What do we need to stop doing?

START What do we need to start doing?

STAY What do we need to keep doing?

Further information

Watch

North Ayrshire and Carnegie Trust UK have created a short film on The Practice of Kindness (Scottish context).

Reflect

As part of its learning on Dignity in Care, SCIE has a learning resource on warmth and kindness, with two accompanying practice scenarios.

Read

Research in Practice has a supervisors’ briefing on Leading with compassion.